"My allegiance is with the inner self

The dark celestial voice of wisdom

Beyond the dust that is this world"

—Agalloch, “Celestial Effigy”

In the beginning, the universe was without form and void, and darkness was upon the face of the deep.

Then, rain began to fall. Somewhere in the distance, a church bell tolled. Heavy, fuzzy riffs erupted from the gloom, and Ozzy Osbourne’s haunted wails heralded the arrival of a demonic entity.

I speak, of course, of the opening of Black Sabbath’s 1970 self-titled debut album. And arguably, the birth of the metal genre, as that album contained the seeds of the entire dark, twisted family tree, with its roots in blues rock and its branches among dead, alien stars.

If you haven’t listened to it, I recommend doing so while you read the rest of this post:

Metal as Tantric, Tantra as Metal

So, what does this have to do with spirituality?

In this essay, I’m going to make an argument that heavy metal, as a genre of music, shares a deep kinship with the spirituality of Indo-Tibetan tantra, and that tantra in turn is metal as fuck. Through this comparison of metal and tantra, I hope to shed some light (or darkness?) on the theme of nonduality—the fundamental truth of nonseparation between you, me, and the universe.

If you’ve yet to be initiated into the mysteries of either metal or tantra, hold on to your latte. It’s going to be a wild ride.

What is Metal?

At the risk of upsetting both metal fans and music critics, allow me to attempt a brief definition:

Heavy metal, or simply metal, is a genre of rock music that emphasizes distorted electric guitars, extended solos, technical virtuosity, complex riffs and song structures, and above all, loudness. Its lyrics often include transgressive elements such as violence, death, and darkness; mythic, supernatural, or occult themes; and the authenticity and integrity of the individual as opposed to conformity and social norms.

The Spirituality of Metal

Famously, some metal bands identify as Satanic. Others engage with pagan, animistic, or mythic themes in their lyrics, or sing about occultism and (black) magic.

Some metal fans earnestly adopt these ideologies and practices as their own. For others, they merely serve as aesthetic window-dressing. For most, I would wager, they constitute a source of personal and creative inspiration.

Metal is the only genre of popular music I know of that regularly employs the power of myth, reaching beyond the personal to the transpersonal realm of gods, archetypes, and the hero’s journey. Whether it’s Ozzy singing about a wizard on that first Sabbath album, or contemporary metal bands inspired by J.R.R. Tolkien (Amon Amarth, Blind Guardian), metal is unafraid to nerd out on some Joseph Campbell, after-school D&D club shit that would embarrass most pop musicians.

Through this combination of musical intensity and archetypal, mythic content, metal aims to transform the consciousness of the listener in a way that I am afraid other musical genres are simply not pretentious enough to attempt.

As Erik Danielsson, frontman of the Swedish black metal band Watain, told poet Michael Robbins, metal “is the form of music through which diabolical energies flow with the most swiftness and potency.”

The best metal bands, in their live performances, enhance this effect through ritual and stagecraft, harnessing the communal experience of a concert to create an experience of transformation. What this looks like ranges from the animal skulls and earnest sage-burning of Wolves in the Throne Room’s opening ritual to the goofy pope hats and pyrotechnics of a Ghost show. Either way, there’s a spirit of using extremity to go beyond ordinary consciousness: in the words of the Heart Sutra, “gone, gone beyond, gone utterly beyond.”

What is Tantra?

This one is going to get me into even more trouble than my definition of metal, because if there’s any subject with more self-appointed gatekeepers than metal, it’s tantra.

Tantra is an esoteric spiritual tradition with its origins in India around 600 CE. It probably started within Hinduism but quickly spread to Buddhism and other Indian religions.

Contrary to popular Western misconceptions, tantra isn’t primarily a sex thing, although some forms of tantra do involve sexual imagery or practices. Instead, tantra is primarily about the use of ritual, mantras, and other yogic practices to transform consciousness, with the ultimate goal of spiritual awakening or liberation.

Transgression and Transcendence

So, what makes tantra different from other forms of Hindu or Buddhist yoga? What makes it uniquely metal?

Tantra uses transgressive imagery—and sometimes, practices—in an uncompromising quest for spiritual awakening in this lifetime.

Early tantric practitioners frequented cremation grounds, drank from cups made of human skulls, consumed taboo substances such as meat and alcohol, and engaged in ritual sex, all of which would have been considered highly illicit in the context of medieval Indian society.

The purpose of these transgressive practices wasn’t teenage rebellion, but the transcendence of dualistic habits of mind, what William Blake might have called the “mind-forg’d manacles” that keep us bound to this world of illusion.

See, from a nondual perspective—that is, one in which there’s no separation between one thing and anything else, and we’re all part of a a universal whole—a beautiful altar decked with incense and flowers is no more or less holy than a corpse or a pile of dog shit. All phenomena are merely appearances within pure awareness; dreams in the mind of God.

While contemporary tantrikas are more likely to visualize these transgressive practices than to physically carry them out, the purpose remains the same.

Thus, like metal, tantra uses intensity and transgression to help its disciples break free from ordinary consciousness. Compared to mainstream spiritual practices, tantra was viewed as both an accelerated path and a more dangerous one.

Wrathful Gods

While metal typically draws inspiration from Western spiritual entities such as Satan or the devil, demons, pagan gods, and so on, tantric practitioners engage with a host of entities from the Hindu and Buddhist traditions.

These include yidams or tutelary deities, “dharma protectors,” dakinis, and nature spirits such as yakshas and nagas. In contrast to more mainstream spiritual practices, tantra often depicts its deities in terrifying “wrathful” or sexualized forms.

In the image of the goddess Vajrayogini above, for example, she wears a garland of human skulls and drinking blood from a skull cup. Like tantra’s transgressive practices, this heavy metal imagery serves to cut through dualistic perception and liberate practitioners from the constraints of ordinary mind.

The Left-Hand Path

The concept of the Left Hand Path, or Vāmācāra, has its origins in Indian tantra, and is particularly associated with the transgressive practices mentioned above. (Recall that the left hand is traditionally considered “sinister”—and anyone who’s been to India knows what you use your left hand for).

More recently, through the influence of Madame Blavatsky (founder of the Theosophical Society), the concept of the Left Hand Path (LHP) has been adopted by Western occultists, who tend to associate it with Satanism, black magic, sexuality, and defiance of conventional social norms.

In this Western sense, LHP ideology has been a significant influence on the metal genre, though the original nondual spiritual impulse behind the Vāmācāra, the impulse toward spiritual awakening, seems to have been mostly lost in translation.

Tantric Music

Like metal, traditional Tibetan tantric music can somewhat jarring to listen to, utilizing dissonance, loudness, and overall intensity to overwhelm the senses. For most Westerners, it is not easy listening. Here’s a performance by the monks of Drepung Loseling monastery. Turn up the volume and give this a listen:

Note the use of loud, dissonant horns and deep overtone chanting. It’s pretty different from Western music, right? I was lucky enough to see these guys perform back when I was an undergrad Religious Studies major, and it kind of blew my mind.

The Practice of Chöd

One instrument used in Tibetan music is the kangling, a trumpet made from a human thigh bone. (How metal is that?) Along with the damaru or hand-drum and the bell, the kangling also plays a role in chöd (“cutting through”), one of the most undeniably metal practices in Tibetan Buddhism and Bön.

In the chöd ritual, the practitioner visits frightening places like charnel grounds or ghost-haunted forests—either physically or in her imagination—and visualizes herself sacrificing her own body to be dismembered and eaten by gods and demons, representing afflictions like ignorance, anger, and dualistic perception. In this way, the yogi becomes fearless in her realization of nonduality.

This theme of dismemberment parallels experiences of shamanic initiation found in indigenous cultures, though unlike a typical shamanic initiation, chöd is undertaken voluntarily.

According to the 19th century Tibetan polymath Jamgön Kongtrül, chöd means

"accepting willingly what is undesirable, throwing oneself defiantly into unpleasant circumstances, realising that gods and demons are one’s own mind, and ruthlessly severing self-centered arrogance through an understanding of the sameness of self and others."

How’s that for metal?

Here’s a video of Geshe Tenzin Yangton demonstrating a chöd practice from the Tibetan Bön tradition:

If you have twenty minutes to spare, I encourage you listen to the words of the chöd ritual (there are subtitles) , and then listen to the song “Prayer of Transformation” by Wolves in the Throne Room:

“Lay your corpse upon a nest of oak leaves

Wrapped in a star shroud repent your flesh

A shadow child dissolves”

Listening to metal isn’t always pleasant. Like walking in a cremation ground or a dark forest at night, it can even be overwhelming or terrifying (a dear friend once had a panic attack at a Wolves in the Throne Room show).

But, like tantra, the point of metal isn’t to be relaxing or pleasant—it’s to challenge you. Engaged intentionally, listening to metal can be a way of overcoming habitual mental conditioning and going beyond ordinary mind.

Metal, Tantra, and the Sublime

Not long ago, I was sitting in a tiki bar in Las Vegas with a friend who is a practitioner in the Western esoteric tradition as well as a fan of the horror genre. We had just visited Zack Bagan’s Haunted Museum—a place I can only desribe as full of wonderfully, sometimes laughably horrible things—and I guess we were trying to make sense of the experience and what it meant to us.

My friend told me he was reading Kant, and brought up the concept of the sublime.

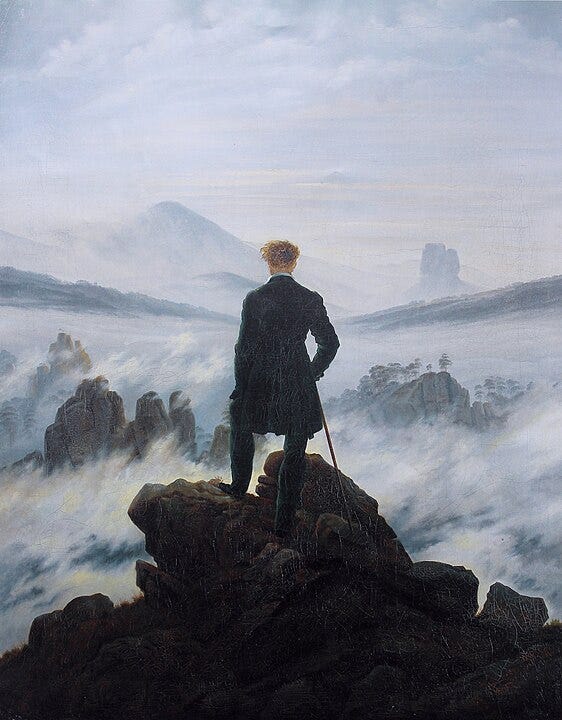

The sublime is usually related to beauty, but unlike beauty, the sublime includes an element of terror alongside awe and wonder. It’s often associated with the destructive or overwhelming power of nature, which we might experience in the form of a storm at sea, or a vast mountain range that dwarfs our human scale.

The sublime was a major theme in Romantic art and literature and continues to inform the aesthetics of metal. Perhaps tantric aesthetics could also be thought of in terms of the sublime—the terrible beauty of a deity like Vajrayogini, dancing on a corpse and drinking blood from a skull, filled with utter love and compassion for all sentient beings—what could be more metal, or more sublime than that?

The German theologian Rudolf Otto used the phrase “mysterium tremendum et fascinans”—the fearful and fascinating mystery—to describe the encounter with the sacred. I can think of no better phrase to describe both metal and tantra.

Tantra, Metal, and Re-enchantment

At this point, you might be wondering what metal and tantra have to do with the overall project of this Substack.

Let me be clear: while I engage with certain tantric Buddhist practices, I wouldn’t presume to call myself a tantrika, and I’m certainly not a scholar of tantra. And although I listen to metal, I’m not the most die-hard of metalheads or an expert on the genre. Instead, I’m someone with enough of a foot in both worlds to make a comparison that others might not see.

Ultimately, I see both metal and tantra as potent avenues for re-enchantment. Through the use of transgression, intensity, and psychoactive, mythic imagery, metal and tantra both provide potent opportunities to bring magic and mystery back to our experiences of reality—much-needed antidotes to the rigid rationalism and materialism that have defined the modern Western world.

Neither metal nor tantra are for everyone. Classically, tantra was said to be for the vira, the spiritual hero who has the courage to transcend duality. Perhaps the same could be said for the true metalhead. But for those who have the will to engage with them, both metal and tantra can be powerfully psychoactive paths to restoring our relationship with the sacred.

In that spirit, here are a few resources for those who wish to explore further:

Destroy Your Safe and Happy Lives: A Poet’s Guide to Metal by Michael Robbins (Harper’s)

Exploring Nondual Shaiva Tantra with Christopher Wallis (Deconstructing Yourself podcast with Michael Taft)

Tantra and Embodied Awakening with Christopher Wallis (ibid)

That’s all for this edition of Mind, Meaning, and Magic. As always, I appreciate your feedback on my writing. What was your favorite thing I shared this week? What would you like to learn more about? Are you a metalhead or a Swiftie? Right hand or left hand path? Let me know in the comments.

Thanks for reading,

Chris Cordry, LMFT

You just revealed a bridge between my son and I that I didn't know was there. Thank you.